NASA has published the results of its agency wide economic impact report, showing that the agency has generated more than $64.3 billion in total economic output during fiscal year 2019, supported more than 312,000 jobs nationwide and generated an estimated $7 billion in federal, state, and local taxes throughout the nation.

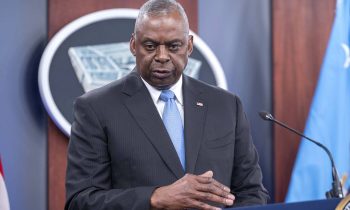

“This study confirms, and puts numbers, to what we have long understood – that taxpayer investment in America’s space program yields tremendous retfurns that strengthen our nation on several fronts – a stronger economy, advances in science and technology, and improvements to humanity,” said NASA Administrator and 2019 Wash100 Award recipient, Jim Bridenstine.

NASA commissioned an economic impact study to further understand how the U.S. economy benefited in FY2019 from America’s lunar and Mars exploration efforts. The study found the agency’s Moon to Mars exploration approach generated more than $14 billion in total economic output in fiscal year 2019.

Additionally, NASA found that each state in the nation has economically benefited through NASA activities, with 43 states having an economic impact of more than $10 million. The agency’s Moon to Mars initiative, which includes the Artemis program, has supported more than 69,000 jobs, $14 billion in economic output, and $1.5 billion in tax revenue.

NASA has more than 700 active international agreements for various scientific research and technology development activities in FY2019. The International Space Station (ISS) has been a significant representative of international partnerships, representing 15 nations and five space agencies and has been operating for 20 years.

Scientific research and development has the largest single-sector impact, accounting for 16 percent of the overall economic impact of NASA’s Moon to Mars program.

“In this new era of human spaceflight, NASA is contributing to economies locally and nationally, fueling growth in industries that will define the future, and supporting tens of thousands of new jobs in America,” Bridenstine added.

Below is a full rush transcript of the press conference by James Frederick Bridenstine, American politician and the Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

MR BRIDENSTINE: Well, It is great to be here, and certainly it’s been a year in the making, but we are now ready to announce not just the Artemis Accords, but that we are starting the Artemis program with some amazing countries that are signatories to the Artemis Accords.

But for a lot of the international media, I want to start by just saying what the Artemis program is. We have been given a direction to go to the Moon, to go sustainably to the Moon – in other words, we’re going to stay at the Moon and we’re going to go with international partners. And in fact, what we’re announcing today is that we want to build the broadest, most diverse, most inclusive coalition of international partners in any human space exploration in ever, and I believe that’s what we are starting today and I think that’s where we are ultimately going to go.

But we’re going with international partners; we’re going with commercial partners. We’re going to learn how to live and work on another world, this being the Moon, for long periods of time. And we’re going to take all of that knowledge on to Mars. So when we go to the Moon sustainably to stay, we call that program Artemis.

And we had a meeting at the last International Astronautical Congress, where we invited all the nations that were participating to come and share with us whether or not they would be interested in participating in the?– in the Artemis program, and the response was overwhelming. We were grateful to see how much interest there is and in joining us in this effort to go to the Moon sustainably and peacefully.

But we thought it was important when we do this that we create a system that is open architecture. And when we talk about open architecture, the way we do docking in space for example, the way we do communication and data and navigation and avionics and environmental control and life-support systems – if we can create standards for the architectures that we build on the way to the Moon and eventually on the way to Mars, we can have nations join us in a very robust way where they can come onboard with whatever they can contribute now and they can grow their programs in the future, because the architecture is open and there’s room for more countries than ever before. And that’s really what the Artemis program is all about.

But we also thought it was important that if all the nations are going to go together to the Moon – and in many ways we’re going to be collaborating and working together – but in some cases we’re going to do things independently, in other cases we’re going to have commercial companies that are part of the Artemis program doing commercial activities – how do we go to the Moon sustainably and at the same time encourage as much transparency as possible for a purpose?

What we are seeking is the peaceful uses of outer space, the peaceful process of getting to the Moon, utilization of lunar resources so that we can live and work on another world for a long period of time, and then enshrine these principles into a document that we all agree to, a document that ultimately is perfectly in keeping with the Outer Space Treaty. And in fact, we call this?– the document, we call it the Artemis Accords. These are the principles that we all agree to.

So it starts with a very basic principle that is enshrined in the Outer Space Treaty that we are going to explore space peacefully, and we think that is so important. And of course, the first step in the exploration of space peacefully is to make sure that nations are being transparent, so that we think NASA has done a really good job being very transparent with what our plans are, what our policies are, sharing those with the world. Transparency ultimately enables trust and enables all of us to work together and collaborate as we go to the Moon.

But it’s not just transparency. It’s also interoperability. Interoperability is how we do all of those things where we interact with each other as independent nations, but at the same time, how do we work together to do things that we couldn’t do alone but all of us together can do more than we would ever be able to do alone. And so that interoperability is key. And part of that interoperability is enabling different nations around the world to be able to provide support to our astronauts when they’re in distress, which of course is also enshrined in the Outer Space Treaty.

And you’re going to hear that theme, I think, today quite frequently. We are operationalizing the Outer Space Treaty and we’re using the Artemis Accords, which are part of the Artemis program, to make sure that when we all go to the Moon together, that we can operate peacefully, sustainably, transparently, interoperably, and then also be able to say, “Look, if one of our astronauts gets in distress, our other countries can come and support us.”

Some of the other, I think, important provisions of the Artemis Accords are the registration of space objects. Of course, we think about that in terms of orbital slots or objects going to specific orbits in space. But we also think it’s important that we register what we’re sending to the Moon, and what you’re sending to maybe Mars, what you’re sending to other planetary bodies. And this could even include asteroids or comets.

And of course, we think that’s important because we have to make sure that we are operating in a way to not interfere with each other so that ultimately, when we go to the surface of another planet, we can be there safely, and dependably, and we’re transparent about what we’re doing and why. And ultimately, it enables other countries, and even private companies, to come to the same planetary body and do so in a way that doesn’t interfere with the activities of others. So registration is critically important for the deconfliction and making sure that we’re going with the norms of behavior. We’re establishing norms of behavior that enable all of us to go and work together.

We also think it’s important that as we go to the Moon and on to Mars and do all of the other space exploration that is important to humanity, that we are sharing the scientific data and information that we get in a very public way. We think NASA has done really well with that over the years. We want to continue that. And we want to encourage all of our partners that when you get new science and new information, new data, share it with the world, just like NASA makes a point to share it with the world.

We also want to make sure that we are protecting heritage sites. We think about the Apollo program, and we want to preserve that hardware for posterity in some cases. In other cases, we might want to bring that hardware back to Earth to study it and see how the radiation of deep space has affected that hardware. So protecting those heritage sites is important.

We also think it’s important to make sure that when countries go to the Moon and other celestial bodies, they’re able to extract resources, which I think is perfectly in keeping with the Outer Space Treaty. We want to be clear: Under the Artemis Accords, there?– we?– there is nobody interested in appropriating the Moon or other celestial bodies for national sovereignty. But we also believe that when we extract resources from the ocean, we can own those resources; whether you are extracting tuna or whether you’re extracting energy, you can extract resources from the ocean, but it doesn’t mean that you own the ocean. And we think that’s true of other celestial bodies, and we’ve put that into the Artemis Accords. And the nations that so far have been wanting to join us in the Artemis program, they’ve all been very accommodating to that.

And then, of course, another big issue that we’re all dealing with as a globe right now is the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines. We have to make sure that we are preserving space for the next generation and the generations that come after that. We have way too much stuff that we need to do for science and discovery and exploration and when space becomes too congested – or contested, in many cases – it prevents us from being able to continue the exploration of space. So we got to make sure that we have these guidelines to mitigate space debris as we move forward together into the cosmos.

I also think it’s important that we recognize that today we’re focused on the Artemis Accords, but it’s also true that there’s – today we’re focused on the eight countries that have signed onto the Artemis Accords, but there’s a lot of room for more countries. And there’s more countries that we anticipate signing on even by the end of the year in a second tranche of nations that come and say, “Hey, we want to be part of the Artemis program. We want to join onto the Artemis Accords,” and we’re very excited about that next tranche. There is room for more.

What we’ve learned on the International Space Station is that all of us can do more when we work together, and really that’s what we’re doing right now with the Artemis program, which we want to make the broadest, most inclusive, most diverse, most transparent, safest program in the history of humanity to do more than we’ve ever been able to achieve before and do it with our international and commercial partners. And that’s really what the Artemis Accords are all about.

MR GOLD: Yeah.Thank you, sir. Just a few things. Yeah, as you’ve pointed out, the Artemis program is meant to be the broadest, most inclusive, diverse human space flight exploration coalition in history. We also wrote the principles of the accords to be as inclusive as possible, that because the accords are the U.S. and the partner nations that are executing the Artemis program, we said, “This is how we’re going to do it. We’re going to abide by the Outer Space Treaty. We’re going to reinforce the importance of the Registration Convention, Rescue on Astronauts,” basically taking all of our multilateral agreements and reinforcing them and implementing our obligations, operationalizing the Outer Space Treaty and the multilateral agreements.

But because we knew not everyone would join, particularly in the near future, we wrote the accords to be inclusive, so that there are no countries that if they’re responsible, spacefaring nations couldn’t abide and shouldn’t already be abiding by every single one of these principles, particularly because most of the Artemis Accords are grounded in the Outer Space Treaty. So we hope that even for nations that don’t sign that we’re establishing a precedent and that we’re influencing the debates and the discussions and future agreements to come in forums like the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and other international dialogue. We want to drive the global discussion via our experiences that we gain on the Artemis program, because good experience, real experience, and facts drive good policy and good regulations.

I’d also like to note that part of the reason international cooperation is so important is not only because it unites us as people, but space exploration is expensive, as I’m sure everyone knows and as I know the administrator is very aware. And it’s terrific to be able to share that burden, to share the expense, share the risk. And what’s been so heartening to see is the increased budgets that many of our partners have been coming forward with to support the Artemis program. Our colleagues in Japan have an unprecedented budget request. Our friends in Europe have record-setting ministerial meetings with budgets that have been driven by Artemis and are going to be incredible contributions that are vital to this global mission moving forward.

Additionally, if your country has more modest means, the Artemis Accords can accommodate that. And that’s why the bilateral structure is so important, that while it’s terrific what we’ve done with the International Space Station and the IGA, the Intergovernmental Agreement is very important, the bilateral structure of the accords allow us to engage with far more nations. And no matter how large or how modest your contribution, the Artemis Accords allow for countries to participate in the program, in building that broad coalition. As the administrator said, it’s the purpose of the program, not only to create peace in space, but to create peace on Earth.

QUESTION: Can you talk a little bit about the role of the Italian Space Agency in this program?

MR BRIDENSTINE: Yeah, so there’s a number of ways that Italy has been very instrumental in human space flight in general. Obviously, Italy is a partner with the European Space Agency. And the European Space Agency is critically important to the operations of the International Space Station. When we think about the development of modules for the International Space Station, Italy has amazing capabilities. And when we think about even the launch to low-earth orbit with rockets, there is amazing capabilities in Italy as well.

So the partnership between the United States and Italy is very strong and robust. It has been for many years. We have had I don’t know how many astronauts from Italy but a number of them, and they’re all the best. They’re all fantastic. I say that; I don’t want to insult any of our other international partners, but we get great astronauts from all of our international partners. But between the astronauts and the ability to create to the habitation modules and of course launch for all kinds of scientific discoveries, the study of the Earth, things like that, Italy has been a great partner of the United States. And Italy has been a big part of the European Space Agency, and so there is a lot of collaborations.

And we look forward to taking all of this robust history all the way to the Moon with Italy. This will be an exciting time for our nations to collaborate once again on a brand new endeavor, which is to go the Moon and on to Mars.

MR GOLD: Well, I think I can add that, Jim, without causing any controversy, the Italian astronauts have the best coffee of any of the astronauts. I think we as a globe can agree on that.

No, I think you hit upon it. I just want to thank Italy that they were one of the first countries to actually agree to sign the Artemis Accords. They are very interested per a Joint Statement of Intent that we executed on a surface habitat on the Moon. And we’re very interested in engaging and look forward to what we can do together.

QUESTION: I wish to know about the Emirati astronauts training at NASA. What will be their role in the Artemis program? And can you talk about the different levels of U.S. and UAE cooperation in the space sector?

MR BRIDENSTINE: Absolutely. So the United Arab Emirates, I think, is an example to the world of how fast a country can create a space agency and then have huge impacts for the discovery and exploration of space.

So I think about just a few months ago the United Arab Emirates launched the Hope Mission to Mars. And of course, NASA is extremely excited to partner with the United Arab Emirates in that mission. And of course, it goes beyond that. As the questioner asked, we have astronauts from United Arab Emirates right now at the Johnson Space Center training to go to the International Space Station. And on top of all of it, United Arab Emirates is launching satellites into Earth orbit and doing great Earth science and exploration in other ways as well.

But here you have a country that five years ago started a space agency for the first time, and now they’ve got astronauts in training. And in fact, they’ve already had one astronaut on the International Space Station, and now they’ve got a mission on its way to Mars as we speak.

And of course, we see the great support that they have from their community, from the nation, and it’s just wonderful to see. And of course, when we announced that we were going to go to the Moon under the Artemis program, the United Arab Emirates was one of the first nations to step up to the plate and say we want to be with you when we go to the Moon.

I will tell you, I would like to see a UAE astronaut on the surface of the Moon one day. There’s a lot that we have to be – we have to work through to figure out who’s doing what and as far as the contributions specifically from each nation in this effort to go to the Moon sustainably. But certainly, I do see a future where the United Arab Emirates would have an astronaut on the surface of the Moon.

MR GOLD: Well, yeah, not much to add to that. Again, appreciate everything the administrator has said. The only thing I would add is at this very moment we have Emirati astronauts training at Johnson Space Center. And as the administrator said – and we both struggle with this – when we talk about new, emerging space agencies we mention the UAE. But their accomplishments are so amazing, it’s almost difficult to consider the country in that category anymore.

So the only thing I would add beyond that is just we appreciate the leadership of the new chairwoman of the UAE Space Agency, Sarah al-Amiri. This is the first time we’ve really been working with her, and what a terrific project to move out of the gate with.

And it’s not only important we work together substantively but work together in policy. And alphabetically the UAE and the U.S. sit together at the United Nations, so we’re just side-by-side both in terms of substantive policy and physically. So appreciate all of the terrific partnership with UAE.

QUESTION: The head of Russia’s Space Agency Dmitry Rogozin said that potentially Russia is likely to refrain from participating in the Gateway projects on a large scale because the whole Artemis program is still U.S.-centric, he said. So do you think that’s Russia’s unwillingness to participate is an unfortunate development for the program, and are you looking at any possibilities to maybe somehow modify the framework of the Artemis Program to make it appear less U.S. centric to other countries including Russia? Do you still expect Russia to join the Artemis Accords at some point? And also if Russia is not participating in the Gateway, will there be any cooperation at all between the U.S. and Russia on the lunar landing itself ?

MR BRIDENSTINE: So I’ll tell you, Director General Dmitry Rogozin has been extremely gracious to me. We have a great relationship. And next month we are celebrating 20 years of American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts living and working together in space. That is an amazing milestone that should never ever be diminished. I mean the relationship has been great.

Even when we go back to the Cold War, we think about the Apollo-Soyuz Program from 1975, and we think about the Shuttle-Mir Program and now, of course, the International Space Station Program; our two nations exploring space together – it is our joint heritage at this point. I would say I remain very hopeful that Russia would join in the Artemis Accords. I remain very hopeful that even if Russian doesn’t – Russia doesn’t join in the Artemis Accords that they would abide by the principles that are enshrined in the Artemis Accords because all we are doing is operationalizing what we have all agreed to in the Outer Space Treaty.

So I think those are important points to make. I would also say that yesterday when we had our plenary with the heads of space agencies, Dmitry Rogozin mentioned he wants to make sure he has – when he has a Russian capsule that’s going to the Moon, he wants to make sure that it can dock with the Gateway. And I’m here to tell you that we are taking what we have learned from the International Space Station, and we are creating those docking standards.

But it goes beyond just docking standards. We want to create international standards for a whole host of human space flight capabilities to include the way we do data, to include the way we do communications and navigation and avionics and environmental control systems and life support systems. We want to make sure that as countries come on board with the Artemis program that the standards are open and available to everybody so that they can very easily on-ramp. And when they do on-ramp, they can even grow. We’re trying to create the most open, transparent architecture in history. That is enshrined in the Artemis Accords, so we remain hopeful that Russia will join us in the Artemis program and, of course, adhere to the very basic tenants that we have all agreed to in the Outer Space Treaty.

I would also say when we think about the Gateway specifically, it in fact does use the intergovernmental agreement that we have been working under with the International Space Station Program.

Now, that intergovernmental agreement, we are going to apply it to the Moon. And so I think that there’s a lot of precedent in how our nations can work together under these types of governance frameworks. And we would welcome to the opportunity to receive what Russia might be willing to contribute to the program, and certainly invite them to share with us what their thoughts are because we do value them as a partner and we hope they value us as a partner, as has been perfectly exemplified now for 20 years on the International Space Station.

QUESTION: What do you want built first when you get there, and how long does it take each of the mission? Does it take two months, two years, because I heard you say you want to live there for a long time. And I know that right now you have only eight countries. How many countries – how do you intend to expand it? Do you want to have, like, the entire country on Earth, or do you want to do a gradual process? And I also know that you work with this ICON construction company in Texas. And I was wondering, do you intend to bring more companies, like international companies from other countries, to do this construction in space?

MR BRIDENSTINE: Yeah, all good questions. So when we go back to the Moon, this time to stay, sustainably, you have to walk before you run. So the first mission to the Moon might be just a matter of days. The second mission to the Moon, we would extend it from there; the third mission would extend from there; and the fourth mission would extend from there. But ultimately, under the Artemis program, what we need to be able to do is learn how to live and work on another world for long periods of time using the resources of that other world. In this case, it’s utilization of the water ice on the South Pole of the Moon. The water ice represents?– well, it’s H20, so it’s oxygen, which is necessary for breathing. It’s H20, which is water, which is necessary for drinking. And it’s hydrogen, which is?– which is a power supply, very prevalent on the South Pole of the Moon, so harnessing the hydrogen for power. Hydrogen is the same rocket fuel that is going to power the SLS rocket, the most powerful rocket ever built, that will take our not just our next man to the Moon, but our first woman to the South Pole of the Moon under the Artemis program.

So we need to be able to use the resources of another world to learn how to live and work for long periods of time. We’re not going to be able to do that on the first mission. But as we build the program with our commercial partners and with our international partners, we believe that we are going to be able to sustain with new technologies and new capabilities for longer than ever before, and we’re going to learn how to do it. And the reason we do that is because we want to go to Mars. We want to lead a coalition of nations to Mars, and we want to be able to explore space together in a very transparent, very safe in a way that avoids conflict. And we believe the Artemis Accords are a way of achieving that.

For your other question about private companies, remember what we’re building. And this is enshrined in the Artemis Accords themselves. We want to build an open architecture system where standards are made public to both international countries but also to private companies. So maybe there is a private company, maybe in Africa or somewhere else, and that private company wants to build something that could be utilized with the gateway or utilized with a service or, I’m sorry, a surface habitation platform on the surface of the Moon. We want the standards to be open and available so that private company, they’re able to?– they’re able to capitalize what they want to build, and ultimately launch what they want to build, and have it be interoperable with other activities that are on the surface of the Moon by the United States, by our international partners, and of course by other private companies. Those standards are necessary so that all of us can do more than we could ever do alone. And I think that’s what makes the Artemis program so exceptionally unique.

QUESTION: Why are you doing this? Why is it necessary? And the other question was: How many countries do you intend to bring together? And do you intend to bring some African countries? We know that when it comes to space, usually it’s U.S., Russia, and the other countries and other continent.

MR BRIDENSTINE: So we see the Artemis program as very scalable. And in fact, countries right now today could sign onto the Artemis Accords, even as we speak, to signal that they want to abide by these norms of behavior and space exploration, and they want to join us in the Artemis program. So we think – when we say it’s scalable, there are countries out there right now that don’t have a space program, but we think that they should have an opportunity to join us in the Artemis program. Maybe they can provide a sensor. Maybe they can provide some kind of widget or capability that we can utilize on the way to the Moon. Maybe they can provide some scientists that are?– that are able to assess the data that we’re getting back from the Artemis program. We think that there’s opportunities for small countries and large countries to come together and all chip in to do magnificent things together when we go to the Moon sustainably. So it is scalable in the sense that small countries to big countries, everywhere in between, we would like to see all the countries of the Earth join into the Artemis program.

But even more importantly, when we do the Artemis program, it’s not just about going to explore the Moon and on to Mars. It’s about agreeing to what are the basic principles by which we do this exploration that enables all of us to do more together; and when we do things independently that we’re not interfering, that we can keep a safe and sustainable environment in space on a not-to-interfere basis, so that we can have peace and prosperity and utilize the resources that come from the Moon and other celestial bodies. So we think that there’s a lot of opportunity.

There’s other reasons to go to the Moon. I love your question. Certainly, we want to learn how to live and work on another world, but when we think about the scientific value – we’ve had subatomic charge particles coming from the Sun for billions of years. They are today on the Moon right where they were billions of years ago because the Moon doesn’t have an active geology or an active hydrosphere. So anything that impacted the Moon billions of years ago is right today where it was billions of years ago. So it’s a repository of data and information of the early Sun and data and information of the early solar system.

So it really is about learning about our own solar system, about our own Sun, and even beyond that from the far side of the Moon, we can do astrophysics in a way that you can’t do anywhere else in the inner solar system because it’s so quiet on the far side of the Moon from an electromagnetic spectrum perspective.

So we believe that there’s a lot of astrophysics, deep space science. We want to learn what the early universe was like. We can do that from the far side of the Moon. We want to see the first light in the universe after the Big Bang. We even want to see the dark ages after the Big Bang and before first light occurred. We want to be able to see that period of time. And the Moon represents those opportunities that are exceptionally unique, and we cannot do that kind of science here on Earth because of the limitations.

QUESTION: Has the U.S. made specific demands of Canada under the Artemis Accords, and what has been the response?

MR BRIDENSTINE: So Canada has been a great partner for the United States. If we go back to the Space Shuttle Program and Canadarm and the International Space Station and Canadarm and, of course, now the gateway Canadarm, Canada signed up to be part of the Artemis program for 20 years, which is something that is exceptionally unique. Canada has never done that before, but they’re so excited about the idea of sending humans to the Moon. They’re so excited about the idea of exploring space together. Of course, this partnership has existed for a very long time not just on the International Space Station. But even before the International Space Station, Canada was the third nation on the planet to launch an object into space.

So Canada has a very robust history in space exploration and we are very excited that the Government of Canada has decided to join the Artemis program and, of course, sign the Artemis Accords which is how we can all go and explore space together peacefully. So it really is, I think, a good time for nations to recognize what we’ve done together already, what we can do in the future, and to recognize that it’s time to even bring on new countries that maybe historically have not explored space with us, and on-ramp countries that maybe don’t even have a space program at all.

MR GOLD: I would just say that Canada is the only partner nation that has their space contribution on the five-dollar bill, so that absolutely makes Canada unique. I want to encourage all nations to do so. It’s terrific exposure for space exploration.

And if I could just continue on with the theme that you mentioned, Jim, that while it’s great to have Canada and our traditional allies with us, what’s terrific is to add those new countries and to see our allied countries working with those new countries. And I would just cite, we’ve mentioned the Hope mission by United Arab Emirates; that was launched by Japan, by a Japanese launcher, with contributions from academic institutions in the United States. And it’s that kind of worldwide partnership that’s so heartening to see and why the Artemis Accords in many ways and this partnership belongs as much to the international community as it does to us.

And if I could just say to our friend in Africa, the Artemis Accords at the time just seemed like a dream as well. We know that space exploration can seem like a dream for many, but that dream can be transformed to reality. We’re seeing it with the Artemis Accords. And to the extent that countries like Canada, United Arab Emirates can partner with some of the smaller nations, like Nigeria that may just be getting into space exploration, that’s terrific to see and it’s all what we’re trying to do and inspire with the Artemis program.

QUESTION: if the President is not elected or the economy struggles, is there danger that the Artemis might be canceled?

MR BRIDENSTINE: So I don’t think so. In fact, I’m very confident that the program is on very solid footing for years to come. And I’ll tell you, we have worked very hard as an agency to get bipartisan, apolitical support from members of Congress and senators in the United States of America. I’ve done a number of hearings on The Hill just recently, and members of Congress on both sides of the aisle have been advocating for and supporting the Artemis program to include – they have funded in a bipartisan way – for the first time since 1972, Congress has funded a human landing system for the Moon. And now NASA is under contract with three separate private companies to build that human landing system that will take the first woman and the next man to the South Pole of the Moon by 2024.

So we have had strong bipartisan support for this activity in the House and the Senate.

We also recognize that if we look at programs of the past that have proven to be very sustainable, the International Space Station is an amazing example. The International Space Station is a collaboration of 15 nations that have been operating it now for all of these years, but we’ve had astronauts from 19 companies. We’ve had experiments from 103 different countries. When we build programs that are international in nature, it results in a sustainable, long-term program. And the President has told us to go to the Moon sustainably. So that means building, and he put it in Space Policy Directive 1: Go with commercial partners. Go with international partners. And so that’s what we’re doing. And we’re building the apolitical bipartisan support inside our country, and we have seen that manifest itself in other countries as well.

Mike mentioned earlier the European Space Agency just announced the largest budget that they’ve ever had in history. The Japanese Space Agency, they’ve just announced that their budget request is the largest that they’ve ever had in history by about 50 percent bigger. So I think we are on solid footing as we move forward, and I think everybody sees the benefits of space exploration.

Look at how we’re communicating right now. Everything is over the horizon. We’re using terrestrial wireless networks that need a timing signal from GPS. We’re using cameras in our computers that were built for a Mars mission back in the early 2000s. And of course, we’re communicating over the horizon with satellites that connect all of us around the globe. All of these technologies are born from space exploration, and this is just the beginning. There is so much more.

So I think we’ve really got that strong bipartisan, apolitical support. We’ve got that international support and strong support from commercial partners as well.

QUESTION: We are running and chasing voters for their preferences, and who understand this thing about Moon – it’s, like, pretty hard, but still we Google it afterwards. do you have any talks or did you? Has your office held any talks with the Pakistani Government on space sector? Secondly, has President Trump been briefed about your wonderful project? And my third question: What extra precautions have you taken for your astronauts in this pandemic?

MR. BRIDENSTINE: Yes. As far as the President Trump’s program. He initiated what we call Space Policy Directive 1, which directed NASA to go to the Moon sustainably with commercial and international partners, and to take all of the knowledge that we get from the exploration of the Moon on to Mars. And so the President briefed us on what to do in this particular case. And of course, he is an amazing advocate for the American space program, and we see that now manifested in our budgets that have bipartisan support.

The budgets that we have right now are supported by members of Congress in the House and in the Senate, by Republicans and Democrats alike, and I have committed to run the agency in an apolitical, bipartisan way in order to achieve that outcome. And I’m very glad that we have, in fact, done that.

As far as the relationship with Pakistan and space exploration, I can tell you I am confident that we have had numerous dialogues. I personally have not, but Mike Gold, who runs our Office of Interagency and Intergovernmental Relations?– or Interagency and International Relations?– I’m confident your office has. Do you have anything to add to that, Mike?

MR. GOLD: We’re actively involved in Pakistan with what’s called the Globe Program, which is an educational activity. And it’s a great way for countries that aren’t traditional partners to gain familiarity with NASA, to inspire students to start getting involved not just in space, but STEM activities – science, technology, math, et cetera. But also I like Pakistan as an example, because NASA data has been used by Pakistan to track groundwater issues.

And just an example as space exploration is important for inspiration and what we learn about the Moon and the solar system. But so much of what we do at NASA makes a difference in people’s daily lives on Earth. And that groundwater project that we executed with Pakistan is a great example of how our work in space can make life better here on the planet.